Despite significant progress in dental care for the population, in recent years there has been an increase in the incidence of odontogenic maxillary sinusitis (OMS), which is associated with the rapid development of interventional dentistry [1, 2]. RFS occupies one of the leading places among inflammatory processes of odontogenic etiology [1–4]. The connection between RFS and dental disease is often underestimated by specialists, especially if it is not obvious, and often RFS is considered to be rhinogenic, which can lead to improper patient management. First of all, this concerns chronic forms of odontogenic sinusitis with its relatively asymptomatic course [4-8].

According to domestic and foreign researchers, PFS accounts for at least 5-8% of the total number of inflammatory diseases of the maxillofacial area [9, 10]. This is explained by the fact that foci of chronic odontogenic infection cannot always be identified by visual examination of the oral cavity. They can also be concomitant with the rhinogenic form of sinusitis and aggravate its course. Often, chronic TFM is detected by chance during an X-ray examination of the bones of the facial skull for another pathology [5, 7].

A common cause of the development of AFM is errors in endodontic treatment of teeth and dental implantation - passing instruments for root canal treatment (root needles, drills, canal fillers, pulp extractors), as well as filling material and implant beyond the apex of the tooth root into the sinus cavity. Less commonly, foreign bodies in the sinus cavity are fragments of tooth roots [1, 2, 5, 12]. The reasons for the development of AFM also include infection of the sinus during surgery with perforation of the bottom of the cavity of the maxillary sinus: most often (up to 80%) with accidental opening of the sinus during extraction and curettage of the hole after extraction of the first and second molars of the upper jaw, less often - during resection of the root apex, cystectomy, removal of impacted teeth, sequestrectomy, placement of a dental implant, removal of tumors in this area [1, 10, 15].

The leading role in the diagnosis of HFRS still remains with radiation research methods. Traditionally, to assess the paranasal sinuses, including the maxillary sinuses, radiography in the nasal-mental projection, survey radiographs of the skull in direct and lateral projections are used. To visualize teeth, orthopantomography or intraoral contact radiography are used, which do not allow reliably assessing the condition of the maxillary sinuses [11-14]. With the introduction of modern high-tech methods of radiological diagnostics - multislice computed tomography (MSCT), cone beam computed tomography (CBCT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) - many doctors began to abandon classical radiological techniques due to their low information content [12-14]. At the same time, the protocols for describing the paranasal sinuses do not always include data on the condition of the alveolar process and the teeth of the upper jaw [11, 13]. This can lead to untimely diagnosis and various local and general complications in such patients [15, 16].

The purpose of the study is to determine the capabilities of modern radiological research methods - MSCT and CBCT - in the diagnosis of inflammatory changes in the maxillary sinuses (MSS) of odontogenic etiology.

Patients and methods

In the period from 2013 to 2015 in the Department of Radiation Diagnostics of Clinical Hospital No. 1 of the First Moscow State Medical University named after. THEM. Sechenov examined 166 patients with maxillary sinusitis of various etiologies. In 110 patients (66.2%) the odontogenic etiology of the disease was confirmed. An analysis of the distribution of patients according to age and gender showed that of the examined patients with TFS, the majority - 91 (54.8%) people - were young and mature, from 21 to 60 years of age. There were 19 (11.4%) patients over 60 years of age; the average age of patients was 48 years (from 21 to 81 years). The majority were female (62 (37.3%) women and 48 (28.9%) men) of working age.

A comparison of the clinical manifestations of odontogenic HFS and the X-ray picture made it possible to conditionally group patients into two groups: 66 (39.7%) patients with an acute inflammatory process in the maxillary sinus had corresponding clinical symptoms of the disease, and 44 (26.5%) patients had complaints from the maxillary sinus no sinuses were presented (the inflammatory process in the maxillary sinus was chronic).

A comprehensive X-ray examination was performed in all cases. All patients underwent computed tomography (MSCT or CBCT): MSCT - 76 (45.8%) patients, CBCT - 90 (54.2%) patients. 122 (73.5%) patients underwent radiography of the paranasal sinuses in the nasomental, semi-axial projections. To clarify the condition of the teeth of the upper jaw, orthopantomography was performed ( n

=166, 100%) and intraoral contact radiography (

n

=12, 7.3%).

When assessing and analyzing diagnostic images, the criteria for odontogenic sinusitis were the following: the presence of a foreign body of metallic density corresponding to a filling material or implant in the sinus cavity; deep caries and signs of periodontitis of premolars and molars of the upper jaw; destruction of the lower bone wall of the maxillary sinuses in the area of pathologically changed teeth.

Results and discussion

Analysis of the results of radiological diagnostic methods revealed signs of RFS in 110 (66.2%) of 166 cases. 66 (39.7%) patients had characteristic clinical symptoms of the disease (headache, low-grade fever, sleep disturbance, a feeling of heaviness in the corresponding half of the face when tilting the head anteriorly, nasal congestion on one side only); these patients were referred for radiation examination by otorhinolaryngologists. The remaining 44 (26.5%) people did not have complaints from the maxillary sinuses; Previously, they were sent for examination by dentists and maxillofacial surgeons for the following reasons: 22 (13.2%) patients - to clarify their dental status, 12 (7.3%) patients - before dental implantation, 10 (6%) patients - for postoperative control after surgical interventions on the upper jaw. In these cases, the identified inflammation of the maxillary sinus was a diagnostic finding.

As is known, acute odontogenic inflammation of the maxillary sinus develops within 1-3 days. Quite often the cause is an inflammatory process of the upper jaw (acute or exacerbation of a chronic one). Such conditions include complications of dental caries, periodontitis, periostitis, osteomyelitis, as well as suppuration of dental cysts or granulomas [7, 8].

Typical complaints of patients with acute maxillary sinusitis were: difficulty in nasal breathing, rhinorrhea, loss of smell, headache and facial pain, a feeling of heaviness in the corresponding half of the face when tilting the head forward, low-grade fever, as well as night cough and sleep disturbances. Odontogenic sinusitis, in contrast to rhinogenic sinusitis, has the following distinctive features: isolated damage to one of the maxillary sinuses, pain in the tooth or in periodontal tissues that precedes the disease, disruption of the facial configuration as a result of swelling of the soft tissues of the cheek and pain on palpation of the anterolateral wall of the maxillary sinus.

In acute sinusitis, x-rays showed thickened mucous membranes, darkening, and fluid levels. In chronic sinusitis, a decrease in sinus transparency was noted.

When assessing and analyzing diagnostic images, the criteria for odontogenic sinusitis were the following: the presence of a foreign body of metallic density corresponding to a filling material or implant in the sinus cavity; deep caries and signs of periodontitis of premolars and molars of the upper jaw; destruction of the lower bone wall of the maxillary sinuses in the area of pathologically changed teeth, as well as partial adentia of the upper jaw in the area corresponding to changes in the maxillary sinus.

During an X-ray examination, in 44 (26.5%) patients with acute maxillary sinusitis, a thickened mucous membrane and/or subtotal darkening with a horizontal fluid level was detected on a plain radiograph. In 78 (47%) patients, there was a total decrease in sinus transparency, of which 38 (22.8%) patients had foreign bodies of metal density (corresponding to filling material) found in the sinus cavity. However, the low contrast of liquid and soft tissues and the summation of shadows made it difficult to objectively assess the obtained radiographs. For additional assessment of the condition of the teeth of the upper jaw, all patients underwent orthopantomography, which did not allow reliably assessing the condition of the maxillary sinuses, and in 13 (7.8%) patients, accurately interpreting changes in the area of the apexes of the teeth of the upper jaw (due to the reflection of the projection layering of complex anatomical structures ).

According to the results of our study, 24 (14.5%) patients showed signs of chronic periodontitis in the area of premolars and molars of the upper jaw (Fig. 1). Deep caries was diagnosed in 4 (2.4%) patients, maxillary cysts in the area of the roots of premolars and molars were visualized in 6 (3.6%) cases.

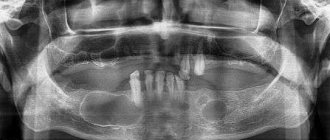

Rice. 1. CBCT. Panoramic (a) and multiplanar reconstructions of the right (b) and left (c) maxillary sinuses of patient M., 37 years old. Diagnosis: bilateral odontogenic chronic maxillary sinusitis. CT signs of chronic granulomatous periodontitis of teeth 1.8, 2.7, 2.8 are noted (in the form of foci of destruction at the apices of the roots, round in shape, with clear, even contours). The lower bone walls of the sinuses are thinned and cannot be traced in the periodontal area of teeth 1.8 and 2.8 (indicated by arrows). In the lower part of the right maxillary sinus, a parietal soft tissue formation of a homogeneous structure with a polycyclic upper contour is determined. The left maxillary sinus is subtotally filled with soft tissue contents of a homogeneous structure with a rounded upper contour.

Filling material was found in 38 (22.8%) patients (Fig. 2). Of these, in 34 (20.4%) patients in the submucosal layer of the lower wall of the sinus, in 4 (2.4%) - in the upper section near the medial wall of the sinus (Fig. 3). 8 (4.8%) patients were diagnosed with dental implantation errors: the tip of the implant was immersed in the sinus cavity, which caused the development of chronic odontogenic maxillary sinusitis, as well as complications in the form of chronic polysinusitis ( n

=4; 2,4%).

Rice. 2. MSCT. Coronal (a) and sagittal (b) reconstruction of the right maxillary sinus of patient K., 29 years old. Diagnosis: right-sided odontogenic chronic maxillary sinusitis. The roots of teeth 1.6, 1.7 and 1.8 are immersed in the cavity of the maxillary sinus. Condition after endodontic treatment of teeth 1.6 and 1.7, with removal of the filling material beyond the apex of the palatal root 1.7. In the area of the roots of teeth 1.6 and 1.7, there is a rarefaction of bone tissue with fuzzy, uneven contours (radiological signs of granulating periodontitis). In the lower part of the sinus, a parietal soft tissue formation with a polycyclic contour is determined; the bony walls of the sinus are not traced in this area.

Rice.

3. CBCT. Sagittal reconstruction, right maxillary sinus. Patient U., 48 years old. Diagnosis: right-sided odontogenic chronic maxillary sinusitis. Teeth 1.6 and 1.7 after endodontic treatment, the filling material is removed from the apex of the roots of tooth 1.6 (the material is located in the bone tissue of the alveolar process and in the submucosal layer of the sinus). A loss of bone tissue is determined in the area of roots 1.6 and 1.7; the bone wall of the sinus is not visible in this area (arrow). In the lower part of the sinus, thickening of the mucous membrane up to 10 mm is determined, in the superomedial part of the sinus an irregularly shaped foreign body of metal density is visualized (corresponding to fragments of filling material). In our study, 30 (18.1%) patients had absence of maxillary teeth in the area corresponding to changes in the maxillary sinus, which also made it possible to judge the odontogenicity of maxillary sinusitis.

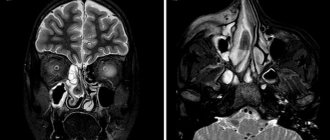

In all cases, computed tomography (MSCT or CBCT) made it possible to accurately diagnose the form of the disease, determine the extent of damage to the sinuses, assess the condition of the lower bone wall of the sinus (identify a violation of its integrity and the communication of the tooth socket with the sinus), determine the source of inflammation in the periodontium, and also identify the presence of foreign bodies in the maxillary sinus. At the same time, the data from MSCT and CBCT were completely comparable with each other, significantly superior to traditional X-ray techniques in terms of diagnostic information content and had such advantages as the absence of superposition, high contrast resolution and the ability to obtain higher-quality reconstructions of images in various planes and 3D images of the area of interest, and also a significant reduction in patient examination time and a reduction in radiation exposure. After computed tomography, treatment tactics were adjusted in 38 (22.9%) patients.

Acute and chronic odontogenic sinusitis

This form of sinusitis is quite painful. This occurs due to the connection between the acute form and inflammation in the area of the tooth root. However, if there are always persistent dental problems, acute sinusitis can develop into chronic inflammation of the antral sinus. The two forms of sinusitis differ in their symptoms.

Acute dental sinusitis manifests itself:

- Severe throbbing pain;

- Swelling around the cheek (can reach up to the eyelid);

- Redness of the nasal wall and turbinates;

- Secretion from the nose is mucopurulent in nature.

In addition, pressing on the affected area may cause pain. Acute dental sinusitis is usually accompanied by fever.

Signs of the chronic form of odontogenic sinusitis are often much less pronounced. Some patients experience symptoms only occasionally, such as occasional headaches.

conclusions

1. High-tech methods of radiological diagnostics (MSCT or CBCT) are a necessary component of the complex diagnosis of HFRS.

2. The use of computed tomography (MSCT or CBCT) makes it possible to determine the cause of AHF and, thus, choose the correct tactics for patient management.

3. MSCT or CBCT should be recommended to patients before and after endodontic treatment of teeth and dental implantation, as well as during surgical interventions on the upper jaw in order to timely identify possible pathological changes in the maxillary sinuses (including asymptomatic ones).

Conflict of interest: The authors of the article have confirmed that they have no financial support/conflict of interest to report.

Acute sinusitis is an inflammation of the sinuses (sinuses) surrounding the nasal cavity that lasts up to 4 weeks.

It usually manifests as nasal congestion, headache, pain or tension in the face.

Most often, acute sinusitis occurs during or immediately after a cold. Less commonly, it can be caused by a bacterial or fungal infection or allergy.

In most cases, antibiotics are not required (unless symptoms of sinusitis persist for more than 7 days in adults and more than 10 days in children).

Synonyms Russian

Acute rhinosinusitis, acute sinusitis, acute sinusitis.

English synonyms

Acute sinusitis, Acute rhinosinusitis, Acute maxillary sinusitis.

Symptoms

There is no single sign by which one can accurately determine that a patient has sinusitis, so when diagnosing this disease, a doctor takes into account all the symptoms and the history of the development of the disease.

The most typical symptoms of sinusitis are:

- nasal congestion,

- headache,

- discharge from the nose, light or yellow, green in color, as well as flowing down the back wall of the throat,

- decreased sense of smell,

- pain, tension, swelling in the facial area, corresponding to the affected sinus: around the eyes, nose, forehead,

- pain in the upper jaw, teeth,

- bad breath,

- cough, especially at night,

- increase in body temperature,

- weakness.

General information about the disease

Sinusitis is an inflammation of the sinuses (sinuses) surrounding the nasal cavity. It is called acute in cases where recovery occurs no more than 30 days from the onset of the disease, subacute - when it lasts from 4 to 12 weeks. If the symptoms of the disease persist without interruption for more than 3 months, it is chronic sinusitis.

Sinusitis is very common at any time of the year, but it is more common in winter.

In fact, it is more correct to talk about rhinosinusitis (from the Greek rhinos - “nose”), since inflammation in the sinuses is always accompanied by inflammation in the nasal cavity itself, which is called rhinitis, or, more simply, a runny nose.

The paranasal sinuses are air-filled cavities in the bones of the skull that connect to the nasal cavity. They are also called paranasal sinuses.

There are 4 groups of paranasal sinuses, and according to their damage, the following types of sinusitis are distinguished:

- sinusitis - inflammation of the maxillary (maxillary) sinuses, located on the right and left sides of the nasal cavity, in the upper jaw,

- ethmoiditis - inflammation of the ethmoid sinuses located between the eyes,

- frontal sinusitis - inflammation of the frontal sinuses located above the eyes

- sphenoiditis is an inflammation of the sphenoid (main) sinus, which is located behind the nasal cavity, close to the base of the brain.

Several sinuses can be affected at the same time, but the maxillary sinuses are most often affected.

The exact function of the sinuses is unknown; it is assumed that they, among other things, are involved in warming and humidifying the inhaled air. They are covered with a mucous membrane with cilia, which produces mucus. This mucus, due to the movement of the cilia, is removed through small holes that connect the sinuses with the nasal cavity. Normally, mucus moves in only one direction, which keeps the sinuses sterile, despite the fact that the nasal cavity connected to them is inhabited by bacteria.

If the mucus exit holes are blocked or the cilia of the sinus mucosa are disrupted, the fluid stagnates and fills the sinuses, causing symptoms of sinusitis: nasal congestion, headache. The accumulation of fluid in the sinuses becomes a favorable environment for the proliferation of bacteria, which makes the disease more severe and complications can develop.

Causes of acute sinusitis

- Infection

- Viral. Most often, acute sinusitis occurs during or immediately after a cold. A cold is accompanied by inflammation of the sinus mucosa in most patients, but the addition of a bacterial infection is noted in less than 1% of cases.

- Bacterial. Much less commonly, acute sinusitis is caused by bacteria. Most often they complicate viral inflammation, although they can also be the primary cause of sinusitis. Sinusitis is considered to be caused by bacterial inflammation if symptoms persist for 7 days or more in adults and 10 days or more in children.

- Fungal. Fungi can cause extremely severe, life-threatening sinusitis. People with weakened immune systems, such as HIV-infected people, are most susceptible to fungal infections.

- Allergy. Swelling of the nasal mucosa due to allergies (for example, to pollen) can block the flow of mucus from the sinuses.

- Anatomical causes, in particular a deviated nasal septum, consequences of injury, or polyps - abnormal growths of the mucous membrane inside the nose.

- Chronic heartburn.

- Chemical agents, including those contained in tobacco smoke, can impair the functioning of the cilia of the sinus mucosa.

Sinusitis can lead to the following complications.

- Meningitis. In this case, the infection spreads to the membranes of the brain.

- Abscesses inside the skull are purulent foci that cause an increase in temperature to 39-40 degrees and severe pain.

- Eye complications. When inflammation spreads to the orbital area, vision may be impaired up to complete blindness.

- Chronic sinusitis, indicated by persistence of symptoms for more than 12 weeks.

Who is at risk?

- Having a deviated nasal septum, polyps in the nasal cavity

- Suffering from allergic rhinitis.

- Suffering from chronic heartburn.

- HIV-infected and other patients with reduced immunity.

- Active and passive smokers.

Diagnostics

The diagnosis of “acute sinusitis” is made based on a study of all symptoms and the course of the disease. There are no specific signs that alone would accurately indicate sinusitis. It is important to distinguish it from the common cold, which can also present with a runny nose and nasal congestion.

Most sinusitis is caused by viruses and does not require antibiotics (as they do not treat viral infections), while bacterial sinusitis is treated with antibiotics. This is why it is important to distinguish between viral and bacterial sinusitis. In practice, however, this is extremely difficult to do, since there are no clear criteria for the addition of a bacterial infection. You need to know that thick, purulent yellow or green nasal discharge is not a sign of a bacterial infection and is often observed with the common cold, which is caused by viruses. Currently, bacterial and viral sinusitis are conventionally defined by the duration of the disease. If symptoms persist for more than 7 days in adults and more than 10-14 days in children, sinusitis is considered bacterial.

Usually no additional examination is required, but in controversial cases it can be useful in making a correct diagnosis.

Laboratory research

- General blood analysis. An increased number of leukocytes may indirectly indicate the bacterial nature of sinusitis.

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). It can be significantly increased with severe bacterial inflammation.

- C-reactive protein is an indicator characterizing the activity of inflammation. With sinusitis it may be elevated, but this is not specific to this disease.

- Rhinocytogram - taking a smear from the nasal cavity, followed by staining and examination under a microscope. Based on the ratio of cells in this analysis, one can judge the allergic or infectious nature of sinusitis, although the reliability of the results is not very high.

- Sowing the contents of the paranasal sinuses. In case of prolonged sinusitis or ineffectiveness of antibiotics, as well as in patients with reduced immunity, contents can be taken from the paranasal sinuses for subsequent culture on nutrient media, where bacteria multiply so that they can be recognized. The most reliable results are obtained with direct puncture of the sinus.

Other research methods

- X-ray of the skull. Allows you to identify thickening of the sinus mucosa or detect fluid in them. Currently, however, it is not recommended because its reliability in diagnosing sinusitis is quite low.

- Computed tomography (CT) of the paranasal sinuses. The most reliable way to study for sinusitis. Particularly useful in case of complications.

- Endoscopic examination of the sinuses. A thin tube is inserted into the nasal cavity to visually assess the condition of the paranasal sinuses. This method can be informative for fungal infections, tumors, polyps, and developmental abnormalities.

Treatment

A disease with moderate symptoms does not require seeing a doctor.

Most patients recover without antibiotics. Treatment in this case includes the use of vasoconstrictors (no more than 3-5 days), rinsing the nasal cavity, inhaling warm steam, warm compresses on the sinus area, painkillers, and taking a sufficient amount of fluid.

Antibiotics are generally only required for severe illness, when bacterial infection is clearly suspected, or when symptoms persist for a long time, and are usually administered for at least 10 days. In approximately 10-15% of patients they do not help, then a puncture of the sinus followed by rinsing it can be used. It may also be indicated if complications develop.

In case of severe purulent complications, operations are performed aimed at eliminating the purulent focus, simultaneously with intravenous antibiotics.

Prevention

- Avoid contact with people with colds, wash your hands before eating.

- Get an annual flu vaccination.

- Proper treatment of allergic rhinitis (incorrect treatment is, for example, uncontrolled and prolonged use of vasoconstrictor drops).

- Use a humidifier at home and ventilate the room (moisturizing the nasal passages increases the resistance of tissues to microbes).

- Do not smoke, avoid contact with tobacco smoke.

Recommended tests

- General blood analysis

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)

- C-reactive protein, quantitative

- Microscopic examination of a smear from the nasal mucosa

- Culture of flora with determination of sensitivity to antibiotics

Literature

- Dan L. Longo, Dennis L. Kasper, J. Larry Jameson, Anthony S. Fauci, Harrison's principles of internal medicine (18th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical Publishing Division, 2011.