Acute toothache is a widespread symptom that signals damage to the nerve located inside the tooth or in the tissues adjacent to it. Painful sensations accompanying the development of the pathological process in such situations arise unexpectedly and cause the patient severe physical and psychological discomfort, negatively affecting his performance, diet, rest and sleep. It is impossible to cope with acute toothache and eliminate the causes that caused it at home: in all cases, without exception, victims require professional dental care. However, there are a number of methods that can quickly and effectively relieve pain for the time required to prepare a visit to the doctor.

Causes of acute toothache

The most common factors that trigger toothache are:

- carious lesions of teeth;

- inflammation of the pulp (pulpitis);

- inflammatory lesions of the periodontium (periodontitis).

With caries, pain appears when eating confectionery, too sour, icy or hot foods. The pain disappears immediately after the irritant that caused it is eliminated.

With pulpitis, the occurrence of pain is caused by bacterial microflora and its toxins entering the pulp. Most often, a person suffering from this pathology begins to experience pain in the evening or late at night. Unpleasant sensations in this case are of the nature of attacks and can radiate to the ear area or to the temple.

The development of periodontitis is accompanied by the appearance of strictly localized, permanent pain caused by general damage to the ligamentous apparatus of the tooth. The pain is intense, since both the tooth itself and the bone tissue localized at the apex of its root are involved in the pathological process. It is worth noting that the discomfort that accompanies the development of periodontitis increases significantly with any load on the diseased teeth.

Along with pulpitis, caries and periodontitis, the causes of acute toothache can be:

- cracks or chips resulting from tooth damage and nerve exposure (including fractures of teeth and their roots);

- improper filling of a carious cavity;

- exposure of dentin tissue in the area of the tooth neck.

Trigeminal facial pain: systematics of clinical forms, principles of diagnosis and treatment

Facial pain, which includes pain on the surface of the face and/or in the mouth (orofacial pain), is one of the most common types of pain. Most often, orofacial pain manifests itself as acute dental pain, which usually regresses after dental treatment. However, in a number of cases, facial pain itself (prosopalgia) is noted, manifested by chronic or recurrent pain, often resistant to various methods of conservative treatment. A kind of primacy in severity belongs to trigeminal facial pain, especially trigeminal neuralgia and deafferentation trigeminal neuropathy, during exacerbation of which the severity of pain is many times greater than the intensity of acute toothache familiar to most people.

Taxonomy of trigeminal prosopalgia

Trigeminal prosopalgia (Greek prosopon (face) + algos (pain)) includes facial pain caused by damage to the trigeminal nerve. From the point of view of topical diagnosis, the development of any form of trigeminal prosopalgia is associated with damage to the peripheral trigeminal neuron - the peripheral trigeminal branches, the sensory trigeminal ganglion (located at the base of the skull), the sensory root of the trigeminal nerve that follows it in the direction of the brain stem, as well as those entering the brain stem sensory trigeminal fibers and sensory nuclei of the trigeminal nerve (

).

Despite the difference in the symptomatology of the clinical forms of trigeminal prosopalgia, the features of facial pain are of primary importance for their differentiation, in some cases manifested by prolonged (constant) pain, and in others in the form of paroxysms of pain. Paroxysmal forms of trigeminal pain are traditionally referred to as neuralgia, and non-paroxysmal forms - trigeminal neuropathy. However, non-paroxysmal postherpetic facial pain is also called neuralgia. These forms of facial pain—neuralgia and trigeminal neuropathy—fundamentally differ in their approaches to treatment.

Paroxysmal trigeminal prosopalgia

Paroxysmal facial pain, lasting from several seconds to several minutes, is manifested by trigeminal neuralgia (typical trigeminal neuralgia), trigeminal neuralgia due to multiple sclerosis, and symptomatic trigeminal neuralgia arising from a tumor lesion of the trigeminal nerve.

Until recently, trigeminal neuralgia, not associated with multiple sclerosis and tumor lesions of the trigeminal nerve, was called idiopathic, i.e. occurring for no apparent reason. However, as it was established as a result of serial neurosurgical interventions, the main etiological factor of typical trigeminal neuralgia is compression of the sensory root of the trigeminal nerve by an atypically located arterial or venous vessel.

Trigeminal neuralgia

Trigeminal neuralgia is the most common form of paroxysmal (paroxysmal) facial pain. It is also considered the most excruciating type of facial pain. It manifests itself as attacks of sharp, high-intensity pain in the area of innervation of the trigeminal nerve. The cessation of an attack of facial pain within a few tens of minutes after taking the anticonvulsant carbamazepine radically distinguishes trigeminal neuralgia from most other types of chronic pain. The symptoms of trigeminal neuralgia undergo significant changes as the pain syndrome increases and regresses, reaching its greatest severity at the height of the exacerbation period.

In secondary (symptomatic) forms of trigeminal neuralgia, which arise from tumor damage to the trigeminal nerve, already at the first stage of the disease symptoms may be observed that differ from the typical clinical picture.

Non-paroxysmal trigeminal prosopalgia

Non-paroxysmal trigeminal prosopalgia, manifested by prolonged facial pain, as well as sensitivity deficit (hypesthesia, anesthesia) in the facial area, includes various clinical forms of trigeminal neuropathy, including postherpetic neuralgia (). Most often, the development of trigeminal neuropathy is associated with obvious etiological factors - trigeminal herpes zoster and traumatic injury to the trigeminal nerve. In some cases, trigeminal neuropathy is one of the early manifestations of systemic diseases, in particular systemic scleroderma, systemic lupus erythematosus, sarcoidosis and Lyme disease.

Traumatic trigeminal neuropathy

It is the main form of trigeminal neuropathy, the clinical signs of which are non-paroxysmal facial pain, sensory impairment (numbness) and, very rarely, motor impairment. As a rule, the acute development of these symptoms has an obvious relationship with local pathological processes and iatrogenic effects in the maxillofacial area.

The first sign of traumatic trigeminal neuropathy is acutely developed sensory insufficiency - from mild hypoesthesia to anesthesia, limited to the innervation zone of the affected sensory branch. Subsequently, paresthesia (a feeling of “pins and needles”) and/or non-paroxysmal pain occurs in the same area of the face. Symptoms of sensory loss that accompany facial pain may persist significantly longer than facial pain. In the affected area, hyperesthesia is often detected, as well as pain on palpation of limited areas of facial skin.

Postherpetic trigeminal neuralgia

Trigeminal postherpetic neuralgia is persistent facial pain and/or burning and itching that persists from the time herpetic lesions develop or occurs several weeks after the lesions resolve (delayed postherpetic neuralgia).

Trigeminal postherpetic neuralgia most often develops in patients over 60 years of age. Its occurrence is usually facilitated by:

- late seeking medical help during the period of acute herpes zoster;

- presence of concomitant pathology;

- complicated resolution of rashes - rashes with a hemorrhagic component and secondary pyoderma;

- pronounced residual sensory deficit (“numbness” of the skin after resolution of the rash).

Deafferentation trigeminal neuropathy (prosopalgia)

Deafferentation facial pain (prosopalgia) is the most severe form of trigeminal lesion, manifested by highly intense facial pain, often resistant to conservative therapy, and severe sensory impairment. Develops as a result of significant damage (destruction) of the peripheral or central structures of the trigeminal system.

The concept of “deafferentation trigeminal prosopalgia”, as a general syndromological definition, was proposed by Yu. V. Grachev and Yu. A. Grigoryan (1995) to designate a special form of facial pain that develops as a result of deafferentation in the sensory system of the trigeminal nerve. The pathophysiological term “deafferentation” (de- + lat. afferentis bringing), literally means the separation of the receptor zones of peripheral nerves from the central sensory structures, due to a violation of the integrity or conductivity of nerve fibers.

Typical peripheral forms of deafferentation trigeminal prosopalgia are postherpetic, tumor and iatrogenically caused facial pain (caused by destruction of the ganglion and trigeminal nerve root), and central are two quite rare forms caused by syringobulbia and medulla oblongata infarction.

Diagnosis of trigeminal prosopalgia

The examination of a patient experiencing facial pain should begin with a systematic medical interview, including clarification of the clinical characteristics of the pain and analysis of anamnestic data (

).

The presence of facial pain requires a detailed study of the function of the cranial nerves, and also makes certain additions to the traditional neurological examination. Objective signs of damage to the nervous system of the face are sensory disturbances in the orofacial region - trigger zones, areas of increased and/or decreased sensitivity (Fig. 2, 3), local autonomic disorders, as well as the presence of local palpation pain.

| Rice. 2. Pattern (model) of sensory disturbances characteristic of exacerbation of paroxysmal trigeminal prosopalgia - neuralgia | Rice. 3. Pattern (model) of sensory disturbances characteristic of exacerbation of non-paroxysmal trigeminal prosopalgia - neuropathy |

When conducting palpation examination of the facial area, it is necessary to distinguish between “neuralgic” and “myofascial trigger” (English trigger).

- Neuralgic trigger points or zones (in patients with trigeminal neuralgia) are hyperexcitable areas of the skin and mucous membrane, with mechanical irritation, including light touch, causing a painful attack. At the same time, strong pressure, usually applied by the patient himself, not only does not cause pain, but in some cases leads to a decrease or disappearance of pain.

- Myofascial trigger points (essentially pain points) are located in the soft tissues of the face in the projection of the masticatory muscles. “Pressing” on them is accompanied by localized or radiating pain.

Establishing a specific form of trigeminal facial pain, which usually requires an interdisciplinary clinical examination, involves excluding a number of forms of orofacial pain not associated with damage to the trigeminal nerve, in particular temporomandibular (arthrogenic and myofascial), symptomatic (ophthalmo-, rhino- and odontogenic) and psychogenic prosopalgia.

Treatment of trigeminal prosopalgia

The complexity of treating patients with trigeminal facial pain is due to the need to determine differentiated treatment approaches due to the ineffectiveness of the use of conventional analgesics for certain forms of trigeminal prosopalgia, the frequent need to change standard treatment regimens and, in some cases, the development of “pharmacoresistant” forms of facial pain that require surgical treatment.

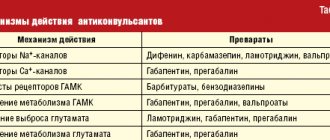

The ineffectiveness of traditional analgesics (for example, NSAIDs) prescribed in connection with the development of trigeminal facial pain is an indication for the use of drugs from other groups, in particular carbamazepine, gabapentin or amitriptyline, which have analgesic activity in a number of forms of prosopalgia (scheme of differentiated therapeutic approaches for paroxysmal and non-paroxysmal trigeminal prosopalgia is presented in

).

Over the past few decades, carbamazepine has remained the most effective and affordable drug in the treatment of patients with trigeminal neuralgia. At the same time, the maximum effectiveness of carbamazepine (as a “monotherapy”) appears in the initial period of the disease. The main indication for the use of carbamazepine is paroxysmal pain, covering the area of innervation of the trigeminal nerve. The daily dose of carbamazepine during an exacerbation of trigeminal neuralgia is usually 600–1200 mg (with a 3–4-time dose of the usual dosage form or 2 times of the retard form), but with uncontrolled use by a doctor it often exceeds 2000 mg/day. As neuralgia regresses, a transition is made to maintenance doses of carbamazepine and its gradual withdrawal when facial pain disappears. If there are contraindications for the prescription of carbamazepine or its forced withdrawal, gabapentin is used as an alternative remedy for the elimination of paroxysmal trigeminal pain.

Gabapentin (Gabagamma) is an anticonvulsant that has an analgesic (GABAergic-like) effect. Obviously, this explains its effectiveness in the treatment of patients with neuropathic pain, including paroxysmal and non-paroxysmal trigeminal prosopalgia. Indications for the use of gabapentin (Gabagamma) are paroxysmal facial pain in trigeminal neuralgia and trigeminal neuralgia caused by multiple sclerosis, as well as subacute and chronic non-paroxysmal pain (including deafferentation) in herpetic and traumatic trigeminal neuropathy. The daily dose of Gabagamma in patients with trigeminal prosopalgia can range from 300 to 1500 mg, with a dosage frequency of at least 3 times a day. Gabagamma is used for a long time and is gradually withdrawn. In general, the use of gabapentin (Gabagamma) is considered safer than carbamazepine and especially amitriptyline.

Amitriptyline is a tricyclic antidepressant that is a norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake inhibitor. This drug is widely used for the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia, especially accompanied by a burning sensation. The analgesic effect of amitriptyline usually develops within 1–2 weeks. To reduce the sedative and anticholinergic effects of amitriptyline, treatment begins with small doses of the drug - 10 mg 2-3 times a day (especially at night), gradually increasing the daily dose (due to evening administration) to 75-100 mg. If amitriptyline is insufficiently effective and facial pain persists, gabapentin (Gabagamma) is indicated.

Treatment of patients with damage to the trigeminal nerve also includes the use of high doses of B vitamins in the form of multicomponent preparations “Milgamma” and “Milgamma compositum”. The composition of the drug "Milgamma" (solution for intramuscular administration) includes 100 mg of thiamine and pyridoxine, 1000 mcg of cyanocobalamin and 20 mg of lidocaine. Milgamma compositum is available in the form of tablets containing 100 mg of benfotiamine and pyridoxine. The effectiveness of Milgamma in the treatment of patients with neuropathic pain is associated with inhibition (probably serotonergic) of nociceptive impulses, as well as acceleration of the regeneration of axons and the myelin sheath of peripheral nerves. The regimen for using Milgamma for trigeminal facial pain includes: prescribing Milgamma in the form of a solution for intramuscular administration - 2 ml daily, for 10 or 15 days, then Milgamma compositum - orally, 1 tablet 3 times a day, for 6 weeks.

Yu. V. Grachev , Doctor of Medical Sciences, V. I. Shmyrev, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor, Scientific Research Institute of Advanced Promotion of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences, State Medical University of the Administration of the President of the Russian Federation, Moscow

How to get rid of toothache?

In order to relieve sudden toothache, it is recommended:

- refuse to eat too rough food, confectionery, ice-cold, too hot or sour foods, drinks (even up to a visit to the dental clinic);

- brush your teeth thoroughly, making sure that there are no food particles left in the cavities formed;

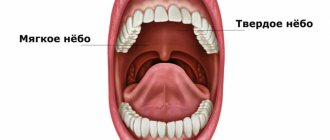

- rinse your mouth with a soda solution (dissolve 5-7 g of baking soda in a glass of heated water, if desired, you can add 6-7 drops of iodine to the solution);

- Rinse your mouth with freshly prepared sage infusion for 15 minutes (to prepare a rinse, add 150 ml of boiling water to a tablespoon of the herb and leave for at least half an hour);

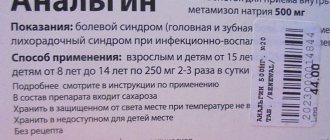

- take orally a small dose of analgin, ibuprofen or other analgesic drugs;

- Apply a piece of ice or a cold compress to the painful tooth or cheek on the affected side.

Light acupressure can be an effective remedy for pain. In most cases, in order to significantly reduce the pain, it is enough to gently massage the small depression located between the lips and nose, or the V-shaped area formed by the index finger and thumb on the affected side.

What should you not do if you have a toothache?

If acute toothache occurs, it is strictly prohibited:

- apply painkillers in tablet form to the affected tooth (most often the result of the described actions is a chemical burn of the epithelial tissues in the affected area);

- take antibacterial agents;

- apply warm compresses and lotions to the tooth or cheek on the affected side;

- try to relieve pain with alcoholic drinks.

In addition, dentists do not recommend resorting to the use of dubious, untested, scientifically substantiated methods and means of alternative medicine.

It is important to understand that the only sure way to deal with acute toothache is to timely seek help from a dental clinic. Modern medications and treatment methods allow dentists to relieve patients of pain in a matter of minutes, and then effectively and quickly cope with the pathological processes that provoke the appearance of pain.

A. V. Stepanchenko, M. N. Sharov, E. M. Neymatov, A. N. SavushkinDepartment of Nervous Diseases, Moscow State Dental University, Moscow'

When describing pain syndromes of the head, face, and oral cavity, various classifications are used, both domestic and international, usually complementary to each other. Our country uses the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10). The basic principles of this classification in the section concerning prosopalgia and cephalalgia form the basis of the “Moscow City Standards of Inpatient Medical Care for the Adult Population” - MGS (1998). However, in these classifications, intended primarily for statistical purposes, cranioprosopalgia is presented only in the most general terms. In clinical practice, the “Classification and diagnostic criteria for headaches, neuralgia and facial pain” proposed by the International Headache Society (IGS) is more often used, captivating with its clarity and simplicity. No less well known is another classification - the International Association for the Study of Pain (IABP), which systematizes and defines pain syndromes throughout the human body, including cranioprosopalgia. In addition, the classification of MAIB concerns mainly chronic pain syndromes, which are mainly dealt with by neurologists.

Domestic classifications, unlike international ones, are focused on identifying nosology, and in many cases successfully complement foreign analogues. This work will compare not only the diagnostic terms of cranioprosopalgia ICD-10, MGS, MAIB, MOGB, but also the working classification for headaches and facial pain used in the clinic of nervous diseases of the Moscow State Medical and Dental University (MGMSU). This classification, its conceptual and terminological apparatus in no way goes beyond the scope of ICD-10, does not pretend to be used in any other way than in the descriptive formulations of textual (diary) records of medical histories and outpatient records. For the same purposes, the terminology of MOGB and MAIB is used, since official medical documents must contain classification terms of regulatory documents of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation or MHS. The greatest attention and appropriate comments will be given to the MAIB and MOGB classifications. These two international classifications have a lot in common, but there are also certain differences, which we will try to analyze and compare with the working classification of headaches and facial pain adopted in the clinic of nervous diseases of the Moscow State Medical University.

Classification of headache and facial pain in the ICD-10 version

Paroxysmal conditions include syndromes, among which the following types of cranioprosopalgia are distinguished.

Migraine.

Migraine without aura (simple migraine), with aura (classical migraine), which in turn is divided into migraine with aura without headache, basilar, equivalents, familial hemiplegic, hemiplegic, with aura in acute onset, with prolonged aura, with typical aura , status migraine, complicated migraine, other migraines (ophthalmoplegic and retinal), unspecified migraine. Histamine headache syndrome (chronic paroxysmal hemicrania, histamine headache in chronic and episodic forms), vascular headache, not classified elsewhere.

Tension-type headache (chronic and episodic tension-type headache), chronic post-traumatic headache, drug-induced headache, and not elsewhere classified.

Prosopalgia is included in the section “Lesions of individual nerves, nerve roots and plexuses”.

Lesions of the trigeminal nerve, which include all lesions of the 5th cranial nerve, including trigeminal neuralgia (painful tic). Atypical facial pain. Other lesions of the trigeminal nerve. Unspecified lesions of the trigeminal nerve. Lesions of other cranial nerves, which include lesions of the glossopharyngeal nerve (damage to the IX cranial nerve and glossopharyngeal neuralgia). Multiple lesions of the cranial nerves (cranial nerve polyneuropathy). Lesions of other cranial nerves (specified and unspecified). Lesions of the cranial nerves, classified in other headings, include: neuralgia after herpes zoster (postherpetic inflammation of the genu ganglion and trigeminal neuralgia), multiple inflammations of the cranial nerves (in infectious and parasitic diseases), classified in other headings - with sarcoidosis, neoplasms and lesions of the cranial nerves in other diseases classified in other headings. Despite the rather pronounced brevity and clarity, postherpetic neuralgia after herpes zoster should not be called trigeminal neuralgia, but ophthalmic postherpetic neuralgia, which reflects the essence of the disease. In trigeminal neuralgia, the identification of a painful tic (it would be more correct to characterize it as “painful”) is now no longer entirely justified, since the use of anticonvulsants has practically eliminated painful hyperkinesis at the height of algic paroxysm.

MGS classification

The terminology of cranio-prosopalgia used in the MGS is close to that in ICD-10. “Damages of the nerve roots and plexuses” also include pathology of the cranial nerves.

- Trigeminal neuralgia

- Atypical facial pain

- Other trigeminal nerve lesions

- Trigeminal nerve lesions, unspecified

- Inflammation of the knee joint

- Neuralgia after shingles Headache syndromes include migraine and other headaches

- Migraine without aura (simple migraine)

- Migraine with aura (classic migraine)

- Migrainous status

- Complicated migraine

- Other migraine

- "Histamine" headache syndrome

- Vascular headache not elsewhere classified

- Tension headache

- Chronic post-traumatic headache

- Headache caused by the use of drugs not classified elsewhere.

The Clinic of Nervous Diseases of the Moscow State Medical University uses a working classification of prosocraniocervicalgia, based on pathophysiological principles and consisting of five sections.

- Neurogenic prosopalgia and cervicocranialgia. 1.1. Paroxysmal type 1.1.1. Trigeminal neuralgia (classical, true or symptomatic) 1.1.2. Neuralgia of the glossopharyngeal nerve (classical, symptomatic) 1.1.3. Neuralgia of the superior laryngeal nerve 1.2. Non-paroxysmal type 1.2.1. Neuropathy of the trigeminal nerve and its branches (mental, lingual, etc.) 1.2.2. Glossalgia, stomalgia 1.3. Combined type 1.3.1. Postherpetic trigeminal neuralgia 1.3.2. Neuralgia of the occipital nerve (greater, lesser). 1.3.3. Cervicalgia.

- Musculoskeletal prosocraniocervicalgia. 2.1. Myfascial prosocranialgia. 2.2. Painful dysfunction of the temporomandibular joint.

- Vegetative-vascular prosocranialgia 3.1. Paroxysmal type 3.1.1. Migraine with aura 3.1.2. Migraine without aura 3.1.3. Migraine variants 3.1.4. Periodic migraine neuralgia (episodic, constant, chronic, other forms) 3.1.4. Temporal (giant cell) arteritis. 3.1.5. Neuralgia of the intermediate nerve (neuralgia of the genu ganglion, Ramsay-Hunt syndrome). 3.1.6. The combined form is periodic migraine neuralgia - trigeminal neuralgia. 3.1.7. Atypical forms. 3.2. Non-paroxysmal type 3.2.1. Painful ophthalmoplegia (damage to the cavernous sinus, Tolosa-Hunt syndrome) 3.2.2. Dental plexalgia.

- Psychogenic prosocranialgia (with neurotic and psychotic disorders) 4.1. Tension headache 4.2. Dysmorphophobia with an algic component.

- Prosocranialgia in diseases of the dentofacial system, ENT organs, multiple lesions of the cranial nerves, cerebrospinal fluid discirculation.

The most diagnostically accurate terminology that corresponds to modern views on the pathogenesis of prosopalgia is presented in the classifications of MOHD and MAIB. Cranioprosopalgia in the MAIB classification is called “Neuralgia of the head and face” and consists of seven groups (neuralgia of the head and face, craniofacial pain of musculoskeletal origin, lesions of the ear, nose and oral cavity, primary headache syndromes of vascular origin and cerebrospinal fluid dyscirculation syndromes, pain of psychogenic origin in the head, face and neck area, occipital and cervical musculoskeletal disorders, visceral pain in the neck area). All these forms are described in the section “Relatively localized pain syndromes of the head and neck.”

The MOHD classification presents thirteen general diagnostic sections - migraine; tension headache; beam (cluster) headache and chronic paroxysmal hemicrania; headaches not associated with structural brain damage; headache due to injury; headache due to vascular diseases; headache due to intracranial non-vascular diseases; headache due to taking certain substances or their withdrawal, headache due to extracerebral infections; headache due to metabolic disorders; headache or facial pain due to pathology of the skull, neck, eyes, ears, nose, paranasal sinuses, teeth, mouth, or other facial or cranial structures, cranial neuralgia; pain due to pathology of nerve trunks and deafferentation pain; unclassifiable headache.

Below we provide a comparison of the terms used by the MAIB, MOGB and in the clinic of nervous diseases of the Moscow State Medical University. When comparing terms, the terms MAIB will be placed first, followed by a dash - the terms MOGB, then, also after the dash, the terminology accepted in our clinic. Where the terms MAIB do not have a close correspondence in the classification of the Moscow State Clinical Hospital or the Clinic of Nervous Diseases of the Moscow State Medical University, the term will not be used after the dash.

Neuralgia of the head and face - cranial neuralgia, pain due to pathology of nerve trunks and deafferentation pain - neuralgia and neuropathy of the cranial nerves

- Trigeminal neuralgia (painful tic) - idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia - trigeminal neuralgia (typical or true trigeminal neuralgia).

- Secondary trigeminal neuralgia with damage to the central nervous system (tumor or aneurysm) - symptomatic trigeminal neuralgia (with compression of the root or ganglion of the trigeminal nerve, with central lesions) - symptomatic trigeminal neuralgia.

- Acute trigeminal herpes zoster - chronic postherpetic neuralgia - postherpetic trigeminal neuralgia. The term MAIB indicates that neuralgia is caused by herpetic lesions, but it can be both in the acute stage and in the remission stage. For the same reason, the definition of “chronic” in the classification of MOHD is apparently unnecessary.

- Neuralgia of the geniculate ganglion (Ramsay-Hunt syndrome) - herpes zoster - neuralgia of the intermediate nerve. The term MAIB is more precise and indicates the structure that causes the characteristic clinical picture, so it should be preferred.

- Glossopharyngeal neuralgia (IX cranial nerve) - neuralgia of the glossopharyngeal nerve (idiopathic, symptomatic) - neuralgia of the glossopharyngeal nerve.

- Neuralgia of the superior laryngeal nerve (neuralgia of the vagus nerve) - superior laryngeal neuralgia - neuralgia of the superior laryngeal nerve.

- Occipital neuralgia - occipital neuralgia - neuralgia of the greater (lesser) occipital nerve.

- Hypoglossal neuralgia - other cases of persistent pain when the cranial nerves are affected are glossalgia (or lingual neuralgia). In this case, the term MAIB cannot be accepted, since with pathology of the motor hypoglossal nerve, sensory disorders, including pain, are not observed. Constant pain in the tongue is usually referred to as glossalgia. The term MOGB is more acceptable in this regard.

- Glossopharyngeal pain as a result of trauma - symptomatic Glossopharyngeal neuralgia - symptomatic neuralgia of the glossopharyngeal nerve. Since secondary Glossopharyngeal neuralgia occurs not only as a result of trauma, the term MOPH is more justified.

- Sublingual pain as a result of injury - other cases of constant pain due to pathology of the cranial nerves - stomalgia. In this case, the comments are identical to those in paragraph 9.

- Tolosa-Hunt syndrome (painful ophthalmoplegia) - Tolosa-Hunt syndrome is a painful ophthalmoplegia (damage to the cavernous sinus). It is more convenient to use the term MAIB, because it indicates, in addition to the eponym, the essence of the pain phenomenon.

- SUNCT syndrome (short-term, neuralgia-like pain with conjunctivitis and lacrimation) - there is no analogy in the MOHD classification - a combined form of periodic migraine neuralgia (neuralgia of the first branch of the trigeminal nerve).

- Raeder syndrome types I and 2 - not included in the classification of MOHD - prosocranialgia with multiple lesions of the cranial nerves.

Craniofacial pain of musculoskeletal origin - there is no direct analogy to this section in the classification of MOHD - musculoskeletal prosocranionervicalgia

- Tension headache, chronic form (headache with tension in the muscles of the scalp) - chronic tension headache (episodic, chronic, atypical) - tension headache.

- Temporomandibular pain and dysfunctional syndrome - dysfunction of the temporomandibular joint - painful dysfunction of the temporomandibular joint (myofascial prosopalgia). We believe that the term used in our clinic is more convenient for practical use.

- Rheumatoid arthritis of the temporomandibular joint - a disease of the temporomandibular joint - systemic arthropathy of the temporomandibular joint. Considering that arthritis of the temporomandibular joint can be caused not only by rheumatoid arthritis, preference should be given to the term MOHD.

Pain in case of damage to the ear, nose and horny cavity - headache or facial pain due to pathology of the skull, neck, eyes, ears, nose, paranasal sinuses, mouth, or other facial or cranial structures - prosocranialgia in diseases of the dental system, ENT organs, with multiple lesions of the cranial nerves, with discirculation of cerebrospinal fluid

- Maxillary sinusitis - headache with acute sinusitis - sinusitis. The term MOHS is preferable, as it indicates painful manifestations during the inflammatory process of the maxillary sinus, but without the addition of “acute”.

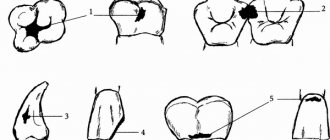

- Odontalgia. Toothache of the first type, caused by a dento-enamel defect.

- Odontalgia. Toothache of the second type (pul pita).

- Odontalgia. Toothache of the third type. Periapical periodontitis and abscesses.

- Odontalgia. Toothache of the fourth type. Atypical odontalgia, dental plexalgia.

- Glossodynia and dry mouth syndrome. In our clinic, the term “glossalgia” is used in cases where allodynia, paresthesia, pain and burning prevail in the anterior 2/3 of the tongue and “stomalgia” if dysesthesia. Sensopathies and senestopathies predominate in other parts of the oral cavity.

- Broken tooth syndrome.

- Inflammatory gum diseases.

- Toothache of unknown cause.

- Diseases of the jaw of inflammatory nature.

- Other diseases of the jaw of unspecified nature.

From 2 to 11 points, the terms MAIB correspond to the same term MOGB - headache or facial pain due to pathology of the teeth, oral cavity or other facial or cranial structures. Similar terminology is used in our clinic for non-core hospitalization or sudden development of pathology of the dental system. Such patients are transferred to dental clinics.

Primary headache syndromes caused by vascular disorders and cerebrospinal fluid discirculation - migraine, cluster headache and chronic paroxysmal hemicrania

- Classic migraine (migraine with aura) - migraine with aura - migraine with aura.

- Project migraine (migraine without aura) - migraine without aura - migraine without aura (simple form).

- Variants of migraine - familial hemiplegic migraine, basilar migraine, ophthalmoplegic migraine, retinal migraine - migraine variants.

- Carotidynia has not been encountered in the practice of our clinic.

- Combined type headache - migraine without aura, chronic tension headache - tension headache.

- Cluster headache - cluster headache with indefinite frequency, episodic cluster headache - periodic migraine neuralgia.

- Chronic paroxysmal hemicrania, non-remitting forms or variants are other forms of periodic migraine neuralgia.

- Chronic paroxysmal hemicrania, remitting forms or variants - chronic paroxysmal hemicrania - tension headache.

- Chronic cluster headache - Chronic cluster headache is a permanent form of periodic migraine neuralgia.

- The “cluster-tic” syndrome is not found in the classification of MOHD - a combined form (periodic migraine neuralgia - neuralgia of the first branch of the trigeminal nerve).

- Post-traumatic headache - chronic post-traumatic headache after a significant head injury or in the presence of supporting symptoms, minimal head trauma without supporting symptoms - prosocranialgia with discirculation of cerebrospinal fluid of post-traumatic origin.

- Jabs and Joults syndrome - idiopathic sudden headache - atypical headache (tension headache).

- Temporal arteritis (giant cell arteritis) - giant cell arteritis - temporal arteritis.

- Headache associated with low cerebrospinal fluid pressure - headache caused by a decrease in cerebrospinal fluid pressure - prosocranialgia due to discirculation of cerebrospinal fluid.

- A headache that does not have specific diagnostic features is an unclassified headache - an atypical headache.

Pain of psychogenic origin in the head, face and neck - psychogenic cranioprosopalgia

- Hysterical or hypochondriacal pain in the head, face and neck - there is no direct analogy in the MOHD classification - psychogenic headaches.

- Headache of psychogenic origin in the head, face and neck, associated with depression - a headache type of tension headache that does not meet the criteria listed above - psychogenic headaches.

Suboccipital and cervical pain of musculoskeletal origin - headache due to pathology of the skull, neck or other cranial structures

- Styloid process syndrome (eagle syndrome) - there is no analogy in the classification of MOGB - symptomatic neuralgia of the glossopharyngeal nerve.

- Cervicogenic headaches - headache or facial pain associated with disorders in the head, neck, etc. - cervicalgia.

- Further, the MAIB classification presents pain syndromes in the neck area caused by tumors and tuberculosis, which, in our opinion, are not within the competence of a neurologist, and therefore are not considered in this work. There is no direct correspondence in the classification of MAIB to such MOHD terms as headaches not associated with structural brain damage; headache due to taking certain substances or their withdrawal; headache due to brain infections; headache due to metabolic disorders.

When comparing these two most well-known international classifications of headache and facial pain, it should be noted that both of them contain definitions that are important in diagnostic terms, a description of diagnostic criteria, and the identification of certain pain syndromes that are little known to practitioners in our country. Both classifications are of great value in the general orientation of the doctor in the diagnosis and treatment of cranioprosopalgia. At the same time, some diagnostic techniques seem overly formalized; entire sections of headaches are of interest only in a differential diagnostic sense (headache due to metabolic disorders or ENT pathology).

When preparing medical documentation, we use the diagnostic terminology set out in the “Moscow City Standards of Inpatient Medical Care for the Adult Population” recommended for healthcare institutions in Moscow (1998). It is advisable to indicate the severity (moderate, intense), as well as the phase of the chronic pain syndrome (status, prolonged exacerbation, beginning remission), and the suspected or proven etiology - post-traumatic, vascular, post-infectious, metabolic, degenerative (osteochondrosis of the spine), psychogenic .

Classification terms do not represent something fixed and frozen; they are subject to mutual enrichment, interpenetration of concepts, and therefore comparison of different classifications seems to us very useful. The doctor, for his pragmatic purposes, has the right to choose from various classifications descriptions and definitions that are more suitable for therapeutic purposes. Determining whether a particular cranioprosopalgic or cervicocranialgic syndrome belongs to a certain group (neuralgic, vegetative-vascular or musculoskeletal) also presupposes a strictly defined treatment tactics.

Literature

- Grechko V. E. Emergency care in neurostomatology. - M.. 1990.

- Karlov V. A. Neurology of the face. — M.: Medicine. - 1991. - 288 p.

- Erokhina L. G. Facial pain. — M.: Medicine. — 1973.

- International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, in 3 volumes. - M., 1995.

- Stepanchenko A.V., Grechko V.E., Neymatov E.M. Cranial nerves in normal conditions and in pathology. M.: MNPI. - 2001. - 239 p.

- Yakhno N. N., Parfenov V. A., Alekseev V. V. Headache. - M., 2000.

- Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgias and facial pain // Cephalalgia, 1988.- Vol 8 (Suppl.7).

- Merskey H., Bogduk N. Classification of chronic pain. Seattle, IASP press. - 1994. - 222 p.